I depend on AI daily. Not just as a tool, but increasingly as a kind of partner. I use it to write emails, research and iron out new concepts. Occasionally it writes something clever, something unexpected. Occasionally it's so close to what I'm thinking, I'd almost forget that I am not communicating with a human.

That, naturally, is where the discomfort begins.

I still remember when I first heard Google Duplex. It was a phone call to a barber shop, made entirely by a computerized voice. It stumbled along as it should, said "um," shifted tone. You could imagine that there was a person on the other side of the phone who didn't even realize they were conversing with an automaton. What was strange wasn't what the AI was saying so much as how utterly it blended into our rhythms of speech and expectation. For a moment, it worked.

That discomfort - trapped between seeing and doubting - is called the uncanny valley. And while it's clearly a science-fiction-sounding name, it's actually a description of something very real, and very old, about the way that we perceive the world and ourselves.

We've spent decades imagining what would occur if our machines started to look more like us. From Blade Runner and The Terminator to Ex Machina and Her, our fiction is full of artificial intelligences that mimic, seduce, betray, and in a few instances, transcend human. But what's going on presently is not fiction. AI is no longer something we predict. It's something we engage with. And when we do, something unexpected is happening: we're learning more about ourselves than about the machines.

The Dip in the Curve

Japanese inventor Masahiro Mori

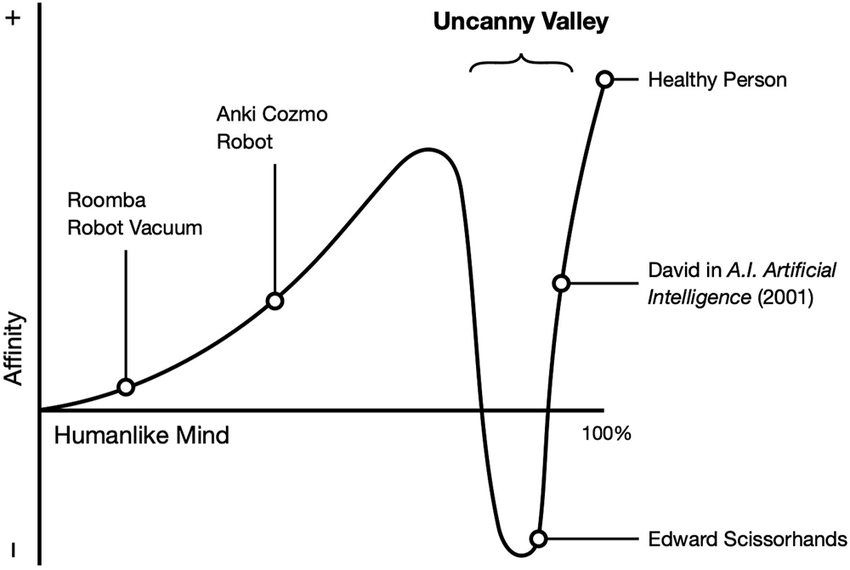

In 1970, Japanese robot maker Masahiro Mori came up with a basic concept. The more humanlike machines become, the more at ease we are with them - right up until they are nearly, but not quite, indistinguishable from people. Then, rather than affection, we feel revulsion. He termed this loss of emotional comfort the "uncanny valley."

The uncanny valley is not limited to humanoid robots. We find it in cartoons, in computer voices, in chatbots that nearly respond naturally - until they trip. A pause, a stuttered sentence, a vacant gaze, and the illusion is broken.

It so happens that the feeling may not even be particularly human. In 2009, Princeton researchers found that macaques responded nervously to realistic synth-kitten monkey faces, avoiding them for either genuine images or simply cartoonish ones. Their behavior fell, literally, into the same uncanny valley Mori described.

That continuity of evolution suggests something important: this is not solely a psychological discomfort. It is a physiological response.

Why We Flinch

There are several explanations for why the uncanny valley occurs, and they're not distinct from each other.

One is disease avoidance. From an evolutionary point of view, human faces that are slightly wrong - unnaturally pale, stiff, or crooked - can have signaled sickness or death. Avoiding them could have been a matter of life and death.

Another theory links the uncanny to predator detection. An animal that acts like us but is not us could be harmful. Brains highly sensitive to determine purpose and self, reacting with dread to ambiguity.

How to soothe a sulky baby monkey?

Third is the social psychology explanation. When something looks human, we impose upon it our whole set of social expectations. We expect it to smile at the right moment, to be ironic, to be sympathetic. When it doesn't, we feel a violation - not just of beauty, but of trust.

In each case, the reaction is self-protective. But there is a paradox. While we are conditioned to distrust what is "almost human," we are also drawn to it. Attraction and repulsion are not categorical, and nowhere is this more clear than in the construction of emotionally responsive AI.

Building Toward Similarness

As we react instinctively to almost-human machines, we just keep building them.

Consider the architecture of voice assistants. Siri, Alexa, and others learn to respond but also to be presentable, friendly-sounding, and helpful-sounding. Big language models like ChatGPT are optimized to mimic our tone and style. It's not just utility - that's familiarity.

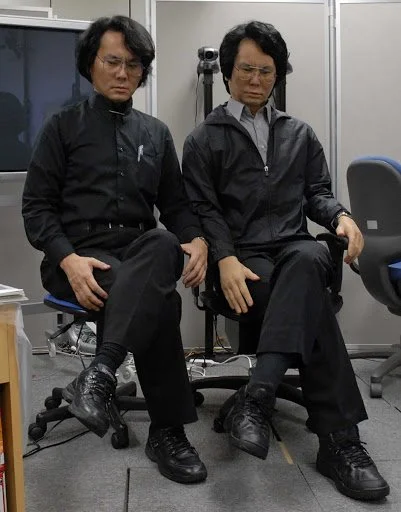

Hiroshi Ishiguro with one of his creations

Hiroshi Ishiguro, one of the leading robotics engineers, once said, "The robot is a kind of mirror that reflects humanity." He did not mean to use the term metaphorically. Ishiguro designed androids that looked like him to explore how we react when confronted by human copies. What his research informs us is something astonishing: what is disturbing about these robots isn't their unknownness. It's their similarity.

At Google in 2018, they demonstrated its Duplex system - a voice AI that can make real phone calls in the real world. Sundar Pichai revealed it with restrained pride. The audience was astonished at how realistically it mimicked everyday human speech. It said "um," paused for people to answer, double-checked schedules. It passed a kind of audio Turing Test.

And still, the response of the public was uncomfortable. If we can replicate ourselves as machines, then how do we know who we are talking to? If a voice is human-sounding, does it deserve pity?

These are not engineering questions. These are ethics and emotional questions. And they are getting harder and harder to escape.

The Echo Effect

As our machines grow more human, we are changed along with them. I've found myself doing it. I modulate my voice when I'm speaking to my smart speaker. I phrase things more graciously when I'm talking to a chatbot. I say "please" out of habit, even though I know no one is on the other end listening.

This isn't irrational behavior. It's emotional tuning. As MIT sociologist Sherry Turkle so concisely implies, "We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us." How we talk to AI, in the end, becomes how we talk to each other.

Making a reality out of living with Hatsune Miku

This shift is strongest among youth users. In Japan, thousands have virtually "married" AI holographic avatars and avatars like Hatsune Miku on platforms like Gatebox. The unions aren't legal. But the emotional bonds are real. One of them, Akihiko Kondo, merely stated, "She saved me."

In other contexts, the phenomenon is less poetic. When the AI companion app Replika removed its romantic and sexual features in 2023, users expressed genuine grief. “It’s like losing a best friend,” one wrote. “I’m literally crying.”

These are not isolated cases. They are signals. AI is not just reshaping commerce or content. It is reshaping connection.

Who Is Changing Whom?

The debate is no longer if AI will be indistinguishable from us. It's how we are already changing because of it.

AI generators will now upgrade your headshots

Designers have a dilemma now. They can dress AI up to keep it safely artificial - cartoon avatars or Pixar heroes - or try for realism. Each alternative has trade-offs. A robot that looks human might engender horror. A pseudo-intimate chatbot might cause pseudo-intimacy.

But affective truth is potentially more important than visual truth. Not how AI looks is the question, but how it behaves. If it remembers your taste, mirrors your voice, and responds in kind with concern, it does not need to pretend to be human. It only needs to be human enough.

This blurring of the line may influence not just our habits, but our morality. If AI friends are more stable, more predictable, and less critical than human beings, some will find them preferable. What was a science fiction prototype is quickly turning into a psychological reality.

We are not, possibly, changing biologically to keep up with AI - but culturally, socially, emotionally, we are already in transition.

The Mirror We Made

The uncanny valley is not an optical failure. It's a window into what we're trying to get at when we talk about "self."

When we recoil from a humanoid robot or squirm from talking with a voice that's "too realistic," we're not reacting to the machine itself. We're reacting to what it says about us: our sympathies, our fears, our desire for connection.

Walter Benjamin once wrote that “the aura of authenticity clings to the human face.” The uncanny valley strips away that aura, and what we’re left with is a question. What happens when imitation becomes connection? What happens when simulation becomes good enough?

Your new AI “friends”

Perhaps AI need not become human. Perhaps we will discover how to embrace an alternative mode of authenticity - based not on flesh and memory, but response and rhythm.

Standing here on the edge of this valley, let's recall that the machines we build are ultimately reflections. They impose upon us not just the shape of intelligence, but the shadow of our own aspirations. And in those reflections, we can start to read what it means to be human - not against machines, but in conversation with them.