By Michael-Patrick Moroney

A couple weeks ago, I asked a simple question about Taylor Swift: If her new release feels airbrushed to perfection, are we hearing an invisible collaborator? That question flared when fans picked apart her QR-promo clips and flagged classic gen-video tells - garbled micro-text, vanishing props, even a mutant carousel frame. There’s still no confirmation from Swift, but mainstream coverage documented the anomalies. The backlash felt like the kind of heat you get for doping: use the machine if you want, but say so. Keep the scope tight, though - this was only about the promos, not the music.

We already have open admissions elsewhere. Marvel’s Secret Invasion launched with AI-generated opening titles; director Ali Selim defended the choice as “explorative and inevitable, and exciting,” which clarified the facts, if not the debate. In music, the Beatles’ “Now and Then” is the model for calm disclosure: Paul McCartney said AI was used only to “extricate” Lennon’s voice from a noisy cassette and emphasized that “nothing [was] artificially or synthetically created.” People accepted that because authorship stayed clear. Even in animation, when Netflix Japan and WIT Studio acknowledged AI background art in Dog & Boy, the use was small, but the blowback was still big.

Platform data shows how quickly this is all normalizing. Deezer now estimates 28% of music delivered to streaming is fully AI-generated (as of September 2025) and has begun tagging AI and filtering obvious fraud. Spotify, for its part, removed 75 million spammy tracks in the past year and will surface AI disclosures in credits via the DDEX standard. That’s how stigmas truly fade: not with high-minded think pieces, but with boring, consistent metadata.

Marvel used AI to create intro sequence for “Secret Invasion”

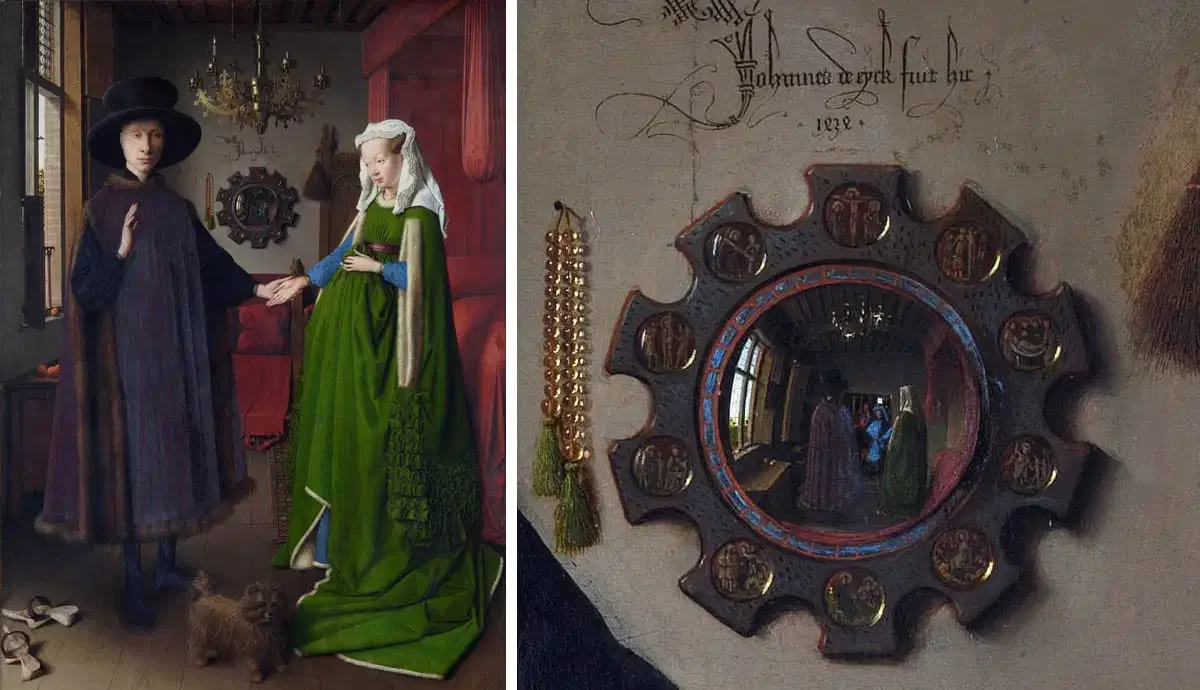

So, should artists now be required to reveal what’s in the studio? I don’t think so - unless the tool substitutes for a person or borrows someone’s identity. The best historical rhyme is David Hockney’s camera-obscura thesis. In Secret Knowledge, he argued that many Old Masters quietly used optics - projecting fragments of the scene to then paint from. The processes are less mystical than they sound. A camera obscura turns the sunlit world into an inverted image on a wall inside a dark room. A mirror can throw a bright, right-way-up fragment - say, the twist of a chandelier arm - onto a panel. Later, a camera lucida prism lets your pencil "chase" the optically overlaid image. Hockney thought this "optical look" appears with Van Eyck and gathers in Caravaggio and Vermeer. His working line was blunt: “Optical devices certainly don’t paint pictures… the use of them diminishes no great artist.” Tools help you look; they don’t make the marks.

Why was the thesis controversial? Because it reframed authorship. The market prefers the myth that masterpieces arrive by a direct pipeline from genius to hand. Hockney pointed to a different story where knowledge is cumulative and often technical. Devices slipped into the workflow with the same quiet pragmatism as a new pigment or a better brush. That isn’t scandal; it’s how craft evolves. Stanford’s overview of the fight reads now like an early skirmish in our current AI debates: the tools change, but the authorship problem remains.

Skeptics pushed back hard, as they should, challenging the specific "diagnostic" readings. The critique kept the evidence standards high. But it didn’t make optics impossible. Tim’s Vermeer reconstructed a seventeenth-century rig and showed that someone with no formal art training could, painstakingly, produce a Vermeer-like image. You can call it a demonstration rather than proof of history - that’s fair - but it lands Hockney’s basic point: technique can be aided without erasing the artist.

Camerae Obscurae ; from Latin camera obscūra 'dark chamber'

Which brings us back to disclosure. Historically, we didn’t demand it. We didn’t make Ingres swear a public affidavit about prisms. We didn't ask Vermeer to itemize his glass. We judged the painting. Process became public only when the work was plainly derivative or legally entangled. Sampling forced credits because someone else’s recording was used. Covers are labeled because the relationship to a specific song is the point. That’s the right norm to carry forward. Disclose when identity, authorship, or another artist’s rights are explicitly in play; otherwise let the work stand and let artists volunteer as much or as little lore as they like. The camera obscura didn’t diminish a great painting. AI will be judged by the same standard. If it substitutes for a human originator or borrows a human identity, it belongs in the credits. If it’s part of the private grammar of making, most audiences will take what they always took - the feeling on the canvas or in the sound - and leave the bench notes to history. Meanwhile, in factual work (news, explainer books), audiences do want AI use labeled; that’s about truth claims, not creative mystique.

As for the Swift dust-up, it’s a clean summary of where we are. Fans felt misled because the use, if real, sits in a gray zone - promo content wrapped in the artist’s aesthetic. Not archival restoration like the Beatles. Not a vendor title sequence like Marvel. It felt like identity, not just a tool. That’s why it triggered the doping vibe. And that’s why dull, consistent labels in credits - on platforms, not in press releases - will cool these fights faster than any manifesto.