The Ballad of the Oyster Boy: Abel Kayne’s Brackish Blues

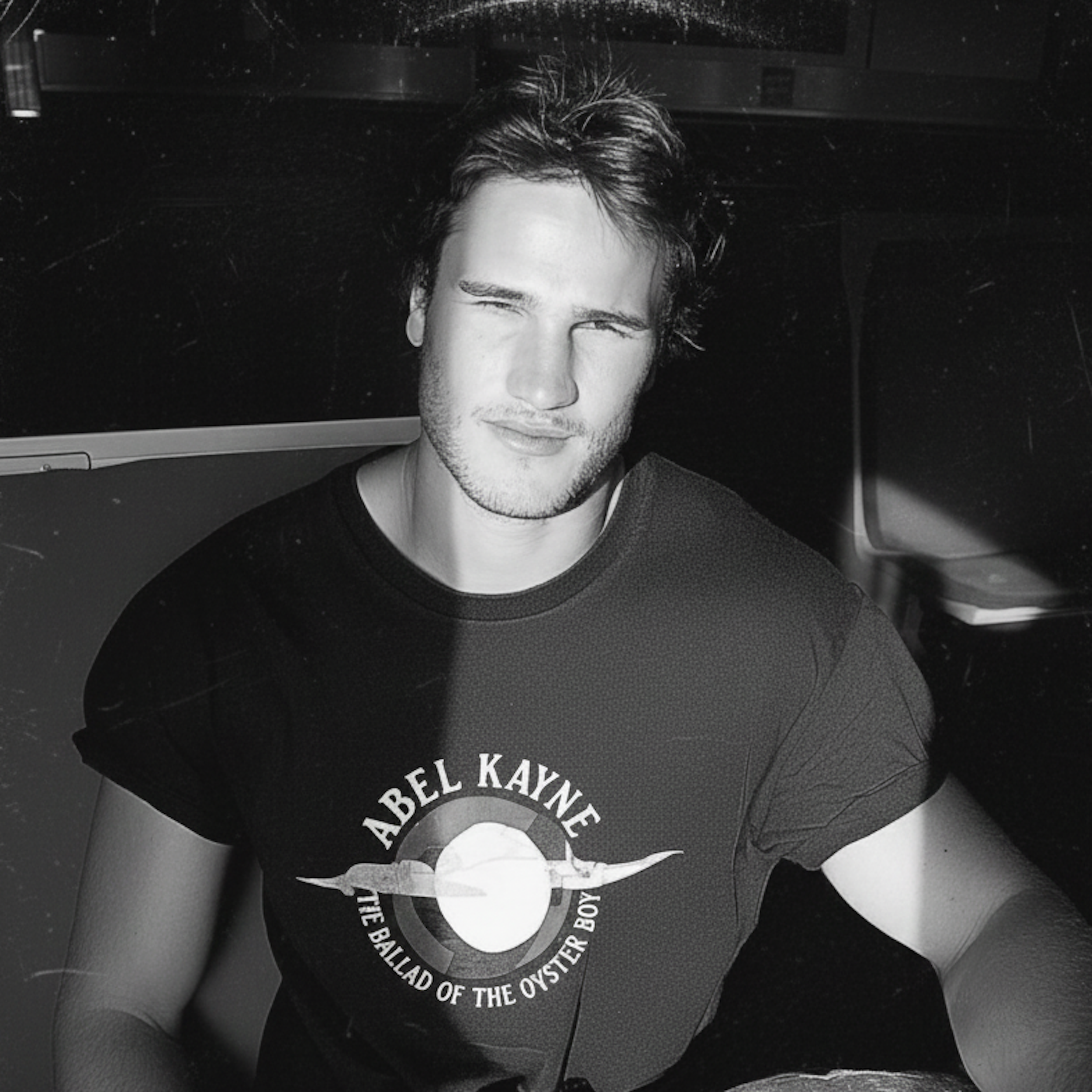

From the high bluffs of Natchez, Mississippi, the river is a moving wall of brown. Nineteen-year-old Abel Kayne grew up watching it slide past below his neighborhood, tugging at barges, history, and anything not nailed down. Now that same pull has taken him 300 miles south to a swaying dock in Gulfport, where the locals call him “OB”—Oyster Boy.

He spends his days on the oyster boats with men whose faces look carved from driftwood, hauling heavy, briny nets until his hands are chewed up. By night he sits on the dock with a battered acoustic guitar, writing songs that sound like they belong to someone twice his age.

Natchez, with its postcard mansions and haunted underside, gave him his first education. His mother ran a riverside bar not far from the bluff edge, on ground where steamboat captains once tied up to unload cotton and drink themselves numb. His father fixed cars and played blues guitar. His grandfather took him down the paths from those high porches to the muddy bank and told him a different kind of story.

“Granddaddy said we had native blood,” Abel recalls. “He said it wasn’t about magic. It was about listening. He taught me to hear the quiet inside the wind. That’s where the music hides.”

The work paid for a rented room, a cheap fridge, and a creeping isolation. To fill the silence—and to catch the eye of the dock foreman’s daughter, a sharp, ambitious girl bound for Tulane—he bought a used guitar. She left for New Orleans with barely a backward glance. “It’s crazy how somebody can break your heart without knowing they did anything,” he says.

Out of that came “Louisiana Memory,” the most naked of his early songs. It opens on a parish of Creole cabanas and slides into pills, liquor, and a waitress tempting him to “step right back into the ring.” In the chorus he undercuts the romance with one line: “Just another American background, Louisiana memory.” When he sings about taking her “to my home in the hickory pines,” he is reaching back to the safer ground above the Natchez riverbank, not some abstract country scene.

If that song is confession, “Shipwrecked” is a warning. Written in his cramped room after boat shifts, it starts with alarm clocks, bills, and “a sea of desperation,” driven by money and fear of failure. The chorus is blunt:

“Shipwrecked, capsized

Swept away, drowning in the modern world.”

The narrator has kids, a mortgage, and four decades of grind behind him. Abel has none of that. He is writing what he sees in the faces of tourists and older men around him. “People come down here with nice watches and shiny SUVs,” he says. “They look like they’re holding their breath. I’m the one who smells like fish guts, but I feel like I can breathe. That song is me telling myself not to trade my cottage for their cage.”

“Tennessee Moon,” the third pillar of his set, reaches into a different corner of the American songbook. It tells of a man who grows up in the country, moves to the city, rides in limousines with debutantes, then admits his heart lives under a “Tennessee moon” with a country fiddle howling in the background. Abel hasn’t spent years in pinstripe suits, wheeling and dealing with millionaires, but he grew up hearing road stories from musicians who did. The song folds their ambitions and regrets into his own tug-of-war between small-town roots and bigger stages.

“It’s about duality,” he says. “My granddaddy was grounded. My daddy liked the flash of the city blues. I’ve got both. You can put me in a suit, but I’m still looking for a fishing pole.”

None of this arrived via algorithm. The break came the old way: by ear. The manager of the Portside Bar heard him playing on the dock one afternoon and watched a couple of fishermen stop instead of heading straight home. A few days later, Abel had a Thursday night slot—tips and beer, and a roomful of people leaning in.

By sunset, the boats rock lazily in their slips and the sky over the Gulf turns a heavy, bruised purple. Inside the Portside, regulars drift toward the corner stage, curious to see what the Oyster Boy has come up with this week. They know the rough outline now: the kid from the Natchez bluffs, the oyster shifts, the Tulane girl, the songs about escape and return.

Out on the dock, Abel Kayne finishes his beer and hoists his scarred guitar. The river that once rolled past his childhood home has carried him to the edge of the continent. For the steamboat captains who drank in his mother’s bar, this coast was the last stop. For the Mississippi Oyster Boy, it feels like the beginning